– S B Agnihotri1

India has set itself ambitious targets for generating solar power. The recent RE-Invest event, held in New Delhi, was an eloquent testimony to this ambition. It was a spectacular event, and the Prime Minister himself, in his Vigyan Bhavan address pointed out the ‘order of magnitude’ change in the thinking. India was now talking of Gigawatts (GW) of solar power and not just Megawatts (MW), and this was not an empty rhetoric. Leading lights of the India Inc, be it private sector, PSUs, Banks lined themselves up in placing concrete pledges before the Prime Minister committing themselves for generation of this power. One must congratulate the MNRE for the sheer magnitude, level and reach of the event.

One could not escape noticing however, that the event essentially ended up becoming a Renewable Power Invest, than Renewable Energy Invest. Even within the Power, the focus was almost exclusively on the solar PV. Other sources were in the ‘also ran’ category, wind power leading the pack, but in the ‘also ran’ silo nevertheless.

While there cannot be any dispute that India should exploit its solar power potential, MNRE needs to seriously ask itself if it has to remain just Solar MW centric, that too grid oriented. Does power availability in itself ensure access, equity or efficiency and, more important, does it address the requirements of energy in coking, domestic lighting, industrial heating and decentralized availability of power?

Ironically, renewable energy holds the key to a sizeable part of the subsidy burden in two of our biggest subsidy guzzling sectors, fertilizers (about 1 lakh crore per annum) and petroleum products about 60,000 crore. It also holds the key to the considerable inequality in the access to and consumption of such basic energy as used in household lighting and cooking, and the need for quality power in rural industry. But before looking at these RE specific solutions, it is useful to take a look at the nature of these inequalities, and put the problem in its perspective.

Access to electricity for domestic lighting:

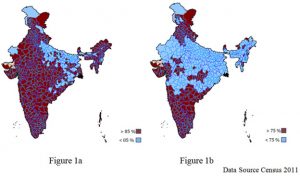

Most of us take electricity for domestic lighting as granted. In urban India this is a fair assumption as Fig. 1a below will show. The number of districts with more than 85% households use electricity for lighting is large indeed. However, as Fig.1b shows, our rural brethren may not be that lucky given that the number of districts where just 75% households use electricity as source for lighting is far less, compared to urban areas.

Percentage of households using electricity for domestic lighting2

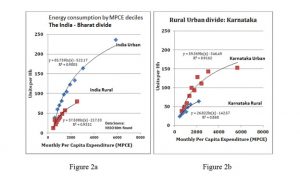

These two figures on access to electricity for lighting purposes, do not reveal the story of the inequality in levels of consumption of electricity. Figure 2a and 2b below gives the relevant information based on NSSO data in terms of levels of electricity consumption in the urban and the rural areas at all India level and within a state.

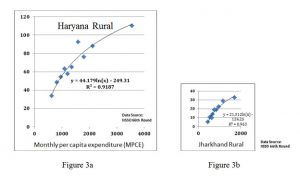

One could clearly see that the energy consumption in the household in the top rural decile is comparable to that consumed by the household in the fourth urban decile. Very interestingly, the divide between the rural and the urban regions of a given state tells one story, but there are considerable inequalities between states as the figure 3a and 3b reveal. The size of the two graphs has been kept proportionate to the levels of energy consumed to give a ready visual appreciation.

What these gaps clearly bring out is that a prosperous person in Jharkhand enjoys far less electricity compare to his counterpart in Haryana. In fact households in the second poorest deciles in rural Haryana enjoy better levels of electricity consumption compared to what the households in the top prosperity decile in rural Jharkhand!

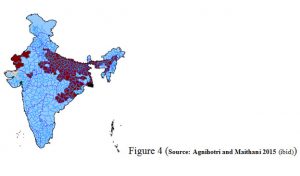

It is also important to notice that the lack of access to energy seems to affect specific clusters. Let us take the example of lack of access to electricity for domestic lighting. Such households almost invariably use kerosene for lighting. Figure 4 gives the map of India, showing the districts where 50% or more rural households use kerosene for this purpose.

Census 2011 data indicates that there are about 8 crore households in the country still using kerosene as source for lighting. A recent survey, done in the course of IIT Bombay’s programme for providing 1 million solar lamps to students who study using kerosene lamps (supported by MNRE), showed that a household typically uses 30-35 litres kerosene per year for lighting purpose. Government pays subsidy of about Rs 33/Litre effectively giving a subsidy of 1000 to 1200 per family per annum. If a onetime subsidy of Rs 1200 is given instead to these households for a modest solar home lighting system, the saving on the kerosene subsidy for the next 5 years (which is the battery life) will be Rs 6000 or a 400% return on investment!! This, one time, home lighting subsidy is not, therefore, a charity. It is an investment which must come from Ministry of P&NG rather than from MNRE. It is worth noting that the annual subsidy bill on kerosene is around 30,000 Crores and MNRE annual budget about Rs 2500 crores.

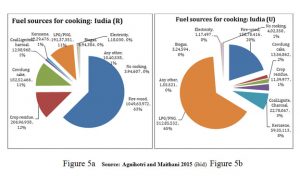

The Bharat – India divide above is equally glaring in the use of fuel for cooking.

As Fig 5a and 5b show, even today, 63% of the rural and 20% of urban households continuing to depend on firewood with far lower efficiency of combustion compared to Bio gas or LPG. More disturbingly the LPG penetration in rural areas is a paltry 11%. Nearly two crore households depend upon cow dung cake as the fuel source. Yet, MNRE programmes on bio gas and improved cookstoves are on the backburner!

Bio manure again represents the same story of a merit good being looked down upon as subsidy. A 2 cubic meter bio-gas plant generates equivalent of about 80 kg of urea saving therefore about Rs.1000 as subsidy per annum based on urea subsidy of about Rs 12 per kg. If Deptt. of Fertilizer provides additional subsidy of Rs 3000 for a 2 cubic meter bio-gas plant they will start saving Rs1000 per annum, year on year from year 4. It is important to promote bio gas on a massive scale even allowing the use of bag digesters which may last only 10 years. With the decision of promoting sale of the Phosphate rich Organic Manure (PROM) through fertilizer industry, the bio gas economics becomes even more attractive and saves subsidy and foreign exchange on import of phosphetic fertiliser.

It is important however to introduce innovations in the bio gas technology. Two efforts are worth mentioning, the first being recycling of the water after separation of the slurry into semi-solids and the liquid portion. This has been successfully tried out by the Bharatiya Agro Industries foundation (BAIF) using a small pump. The semi solid manure can the be phosphate enriched and sold.

A second promising innovation is in the field of dry anaerobic fermentation at higher temperatures e.g. 48-50 degrees. This has been tried out in the food waste digestion e.g. at Akshyayapatra Bangalore, and reduces the digestion time drastically to 17-18 days and thereby bringing down the digester cost as well.

MNRE needs to take serious cognizance of such developments and promote these to a massive scale in tandem with the Ministries of Animal Husbandry and Fertilizer. The Dairy sector has come a long way and today the Central Ministry has a database of all private farms having 50 animal or more. Likewise, the States have a database of all “Progressive Farmers” supported by the scheme of the Ministry to keep at least 10 pedigree cattle. All these must be covered with bio-gas plant on a saturation basis . For this the MNRE needs to think scale and go for a tender-based approach for installation of bio-gas plants in a lot of 50 or 100 plants with 5 year O&M cost being built in. This will bring down the cost, boost rural local employment, and use of organic fertiliser. As the strategy for solar PV has demonstrated that large and steady volume of orders does bring the costs down and reduces, if not eliminate subsidy.

The lack of push to the improved cookstove programme is another anomaly given that even today 10.5 crore rural and 1.5 crore urban households use fire wood as fuel for cooking with consequent impact on environment and pose health hazard to mother and children. Use of other bio mass like cattle dung and crop residue pose even bigger health hazard. Ironically even in Delhi over one lakh households use firewood.

MNRE on the other and has remained preoccupied with creation of standards and stringent (some feel impractical) conditions on the cook-stoves to be supported by them. What we need is a nuanced approach. We need to promote portable forced draft cook-stoves wherever use of fire wood and availability of electricity coincide as in the hilly areas, urban areas and the north eastern states (Agnihotri and Maithani, 2015 ibid). Likewise, we need to push for chimney using earthen chulha in the coastal areas where stagnant air or inversion conditions, that trap the smoke from household chulha, are not a problem. Even use of retrofits like iron grates and twisted tapes can, optimized for a local terrain, improve the efficiency of cook-stoves substantially.

We finally come to bio-mass gasifiers. There is a huge scope for use of these gasifiers at a small scale (typically from 10-500 KW). In telecom tower sector itself, 4-5 lakh reliable, remotely controlled and remotely monitorable bio-mass gasifiers would replace diesel gensets. Further, for rural industrial applications, bio-mass gasifiers of less than 1 MW size are economically viable. These applications range from foundry, aluminum based industry, to biscuit, candle, perfumery making, to sodium silicate and glass manufacturing and dyeing / silk reeling and the ubiquitous puffed rice making. In fact, in some cases the payback period without subsidy is claimed to be between 6-24 months. Bio-mass gasifiers also serve the purpose of boosting manufacturing sector, creating local skilled employment on a sustainable basis, save fossil fuel and pave the way for decentralised energy for villages where grid has not reached.

It is ironical that these gasifiers have not been taken to scale. A probable impediment is lack of standardisation and upgradation of technology. Thanks to the stringent requirement of the telecom tower sector, gasifiers with improved specifications are now available. All that MNRE needs to do is to create specifications, develop vendor base and offer a line of credit. It will be tragic if the sector does not take off.

We have not touched here a huge sector of generating Gigajoules through solar steam and hot water stored at high pressure for industrial and institutional usage. There is a crying need to address this need as the current practices involve a sub-optimal use of fossil fuel. Besides, solar thermal technology is much more compatible with the philosophy of ‘make in India’, needs shorter loan tenures, reduces carbon footprints. But this is a large topic by itself, and need to be debated separately.

To sum up, the excessive emphasis of grid centric GW power generation primarily through solar PV, may not be the optimal policy for the MNRE to pursue. It shifts the focus away from the much needed emphasis on issues of energy access, inequalities thereof and the issue of efficiency. To partly rephrase the great Urdu poet Faiz,

aur bhi gham hain zamaane meiN Gigawatt ke siwa

raahateiN aur bhi haiN faqat Grid ki raahat ke sivaa

mujh se jid kar ke Megawatts, mere mehebuub, na maaNg

1Satish B Agnihotri (sbagnihotri@gmail.com) is a retired IAS officer, and has served as Secretary to Government of India in the MNRE and later as Secretary Co-ordination, in the Cabinet Secretariat. However, the views expressed are personal. Citation: Energy Next, 2015, Vol 5 No 7, Pp 26-28.

2For a more detailed analysis of the pattern of use of electricity and kerosene for domestic lighting, various sources of fuel for cooking and the changes between 2001 and 2011, based on census data see Agnihotri and Maithani 2015: Energy access – tracing the contours of inequality, CSE, New Delhi http://www.cseindia.org/docs/aad2015/Contours-of-inequality2015.pdf.